“I prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, determined to “trap” life in the act of living. ”

People are making more images than ever before. Virtually everyone with a mobile phone has a digital camera to take pictures. Facebook says more than 350 million pictures are posted daily, which is more than the total USA population. This is only on their platforms.

In a moment where photography is readily available everywhere you see, the seminal collection of essays by Susan Sontag (published in 1977) On Photography, are still relevant to think about our relationship with images.

The World is Beautiful (one of the first photographic bestsellers) by Albert Renger-Patzsch. (1928)

Photography as reality

With photography as a way of ‘collecting’ reality in a way we believe as accurate, Sontag warns about the traffic of images as proof, or even substitute, of the real world:

“Photographs furnish evidence. Something we hear about, but doubt, seems proven when we’re shown a photograph of it.””

“The problem is that not only can photographs lie – something we still struggle to believe – but they lie on every level. They lie because they are a selective choice of what reality we intend to show. They lie because most photographs are anything but what people think they are – an accurate representation of what is photographed.”

“It seems positively unnatural to travel for pleasure without taking a camera along. Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, that the program was carried out, that fun was had.”

With social media photostreams, the ultimate attempt to control, frame, and package our lives, this idealized photographic image is visible, with extreme examples such as influencer fake travels.

Sontag comments that “ultimately, having an experience becomes identical with taking a photograph of it”, or as she recalls nineteenth-century aesthete Mallarmé who said everything in the world exists in order to end in a book, she claims: “today everything exists to end in a photograph.”

Tourists heading to Bali to take pictures at the iconic lake in #gatesofheaven have been left stunned to discover it doesn't exist. Getty images.

Photography as a mental frame

It is not only those things we photograph what represents our way of seeing, but the photographies to which we have constant exposure can also frame our responses towards beauty and pain, being capable of diminishing our behavioral and mental responses.

“Knowing a great deal about what is in the world (art, catastrophe, the beauties of nature) through photographic images, people are frequently disappointed, surprised, unmoved, when they see the real thing.”

“To suffer is one thing, another thing is living with the photographed images of suffering, which does not necessarily strengthen conscience and the ability to be compassionate. [...] Images transfix. Images anesthetize.

[...] The vast photographic catalog of misery and injustice throughout the world has given everyone a certain familiarity with atrocity, making the horrible seem more ordinary—making it appear familiar, remote (“it’s only a photograph”), inevitable.”

There are too many images of catastrophes and atrocity but we can’t go numb. We don’t need to see too many of them either. Just evaluate what is real and act accordingly.

Child Swims In Polluted Reservoir, Pingba. Reuters/China Daily.

As Jessica Helfand writes in The Self-Reliance Project series, stories of suffering are now a fixture in our news feeds. But it is images like Fabio Bucciarelli's portrait of a woman in her home in Gazzaniga, Italy, that cut through all the reportage and the rhetoric because they offer us a mirror on something else, something hard to see, perhaps, because it is so familiar.

To stop and reflect for a moment on the universality of one person’s profoundly human expression is an aggregation of everything you know to be true.”

Maddalena Peracchi photographed by Fabio Bucciarelli for The New York Times. March, 19, 2020.

Photography as participation and alienation

The act of photography has a duality of transforming the photographer into both an intimate observer of the frame, catching details that could skip the common eye, and an agent that is detached of its surroundings.

“Photography is also a powerful instrument for depersonalizing our relationship with the world.”

According to Sontag it would not be wrong to speak of people having a compulsion to photograph and turn the experience itself into a way of seeing, supporting the idea that photography interposes itself between us and the ‘real world’ in a way that merely looks like engagement, but is in fact satisfied with a symbolic, morally immobilizing gesture:

“Photographing is essentially an act of non-intervention.”

“A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it — by limiting experience to a search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir.

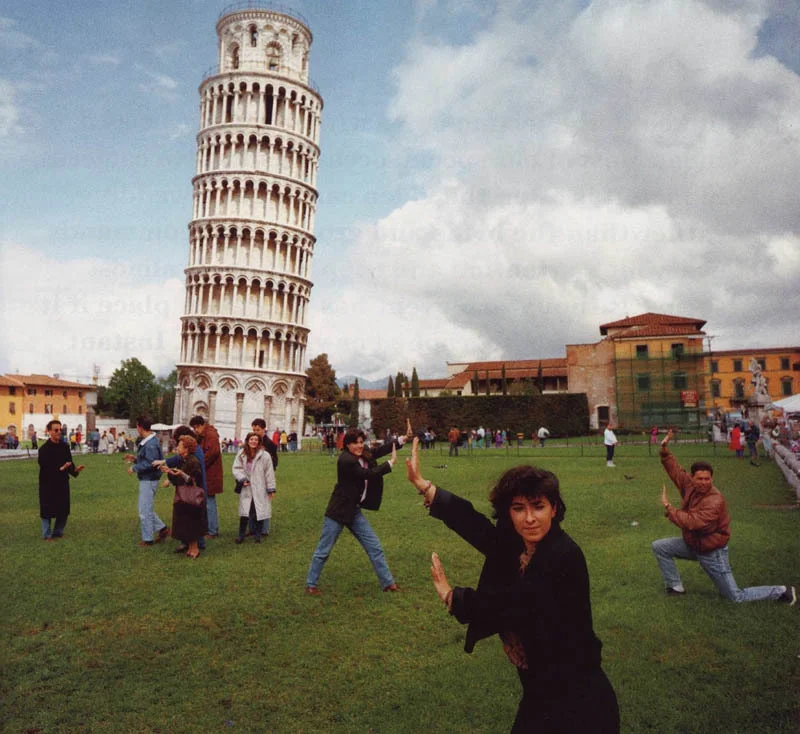

Most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter. Unsure of other responses, they take a picture. This gives shape to experience: stop, take a photograph, and move on. ”

Tourists posing around the Tower of Pisa. Photography credits: unknown.

Photography and time

The capacity of photographs to achieve high detailed images and to “trap life” as it occurs, as mentioned by photographer Cartier-Bresson, gives it the ability to frame a unique reflection of reality during a specific time.

It is a way of collecting unrepeatable moments for future memory when perhaps you can’t remember them as precisely anymore.

“For while paintings or poems do not get better, more attractive simply because they are older, all photographs are interesting as well as touching if they are old enough.”

It is also touching that what you capture will never be the same anymore. Your niece won’t be as little a baby, your face and body will change, the people in the background won’t be there the next time you go.

Photography is both an attempted antidote to our mortality paradox and a deepening awareness of it:

“All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

First cellphone photo ever taken and shared with others online. Philippe Kahn. (1997)

As stated by Paul Strand, your photography is a record of your living, for anyone who really sees. You may see and be affected by other people’s ways, you may even use them to find your own, but you will eventually have to free yourself from them.