Technology is a wonderful, truly, magical thing.

Because of its nature, it’s also quite mysterious. We know how to use it, but we don’t know very much about how it really works.

But computation is made by us, and we are collectively responsible for its outcomes; something to be aware of now that computing impacts virtually everyone, and new kinds of interactions with increasingly intelligent devices and surroundings are being more common in a growing digital world.

Therefore, we should have at least a basic understanding of how computing works, to maximize what we can make and be more mindful of how we shape it.

Based on the wonderful book “How to Speak Machine: Computational Thinking for the Rest of Us” by designer and technologist John Maeda, this article is a distillation of key ideas of the first three chapters of the book, that aims to explain (to nontechie people) the properties of computation, which he describes as being “an invisible, alien universe”.

The Three Alien Properties of Computation

1. Machines run loops:

There’s one thing that a computer can do better than any human, animal, or machine in the real world: repetition.

A computer running a program, if left powered up, can sit in a loop and run forever, never losing energy or enthusiasm. It’s a metamechanical machine that never experiences surface friction and is not subject to the forces of gravity like a real mechanical machine—so it runs in complete perfection.

This property is one of the reasons why it’s tricky when tech companies operate computational systems, that never take lunch breaks or vacations and get down to extreme levels of detail, to know everything about you based on your data (especially when you are unaware of how and what exactly is being collected).

Of course, it is also being used positively, to increase comfort and convenience by anticipating needs and automating processes, (which we all benefit from nowadays) making everyday operations seamless and easy.

You may also take advantage of this relentless property to use it in innovative ways, like the Seoul Digital Foundation, which is employing robots to teach older adults to use KakaoTalk, one of South Korea's most popular messaging apps (if you have explained technology applications to your parents or grandparents, you already know it requires a lot of patience and repetition😅).

A Möbius strip, or loop, is a simple object that can be made out of folded paper and reveals surprising properties as you play with it. How to Speak Machine (2019)

2. Machines get large

Exponential growth is native to how the computer works. This is how the amount of computing memory available has evolved. The same can be said about processing power.

“So when you hear people in Silicon Valley talk about the future, it’s important to remember that they’re not talking about a future that is incrementally different year after year. They’re constantly on the lookout for exponential leaps”

Loops inside loops open new dimensions. In short, it’s a means to open up spaces that are much larger than the ones that surround us as the physical scale of our neighborhoods or cities. There are no limits to how far each dimension can extend, and no limits to how many dimensions can be created with further nesting of loops.

Computation has a unique affinity for infinity; however, you are in complete control when you write the codes and construct the loops to your liking.

“There is a certain comfort as you come to realize that, with eventual ease, you can craft infinitely large systems with also infinitely fine details”. (p.52)

This is unnatural to those of us who live in the analog world, but it’s just another day inside the computational universe.

A magical aspect of the Koch snowflake, a fractal curve, is that its perimeter is infinite but its area is finite. Image: Matthias, LaTeX Stack Exchange (2017)

3. Machines behave like the living (originally stated as machines are living but corrected here)

The traditional approach to creating AI was to teach a computer how to reason through if-then rules. Deep learning (a technique used in machine learning), on the other hand, uses a model of the brain—neural networks in particular—to teach a computer how to think by observing a desired behavior and learning the skill through analyzing repeated behavioral patterns.

For it to work well, the computer needs to observe our behavior. Preferably constantly and interminably.

This is how we can obtain products like Open AI’s GPT-3, a system released last summer that was trained on a vast corpus of text and that can create text to order that is close to writing created by people, based purely on pattern matching and analysis at massive scale.

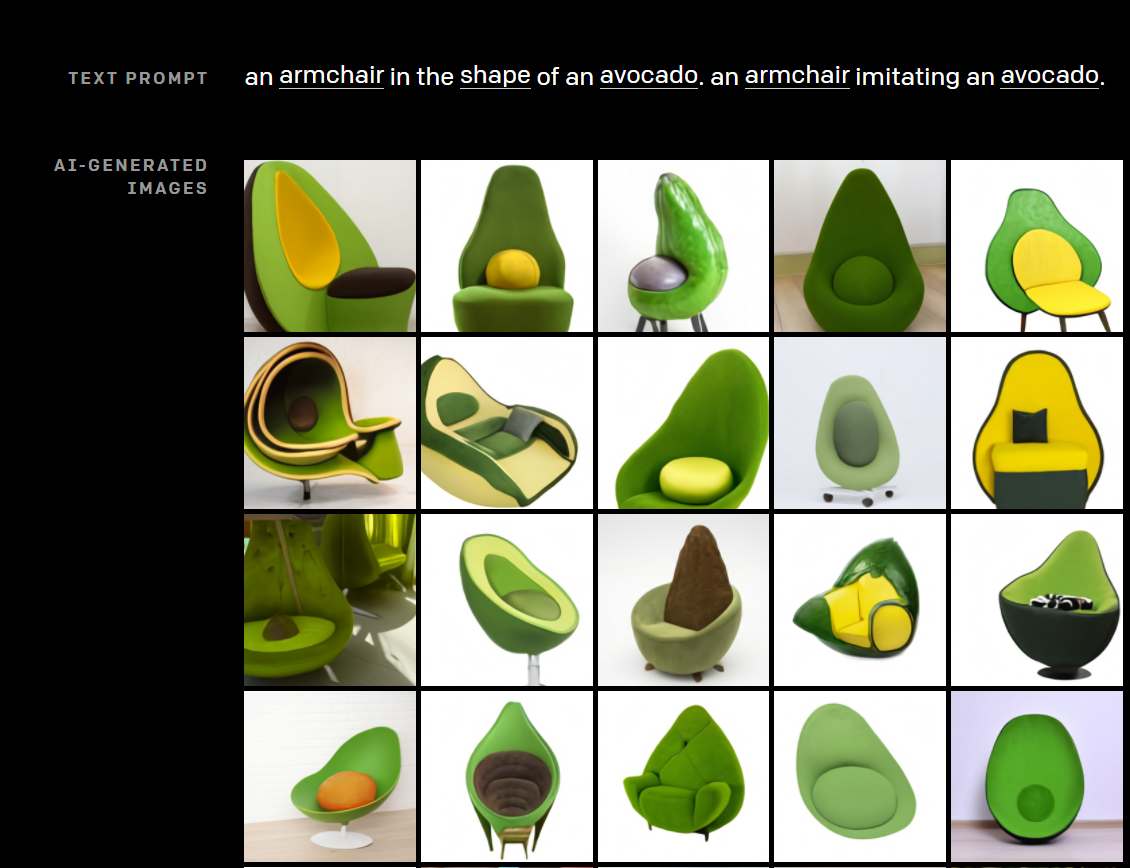

OpenAI recently launched DALL·E, a 12-billion parameter version of GPT-3 trained to generate images from text descriptions, using a dataset of text–image pairs. OpenAI website (2021)

Computation’s potential for connection, not only allowing them to process massive amounts of information but facilitating machines that connect and collaborate at speeds that fast surpass ours, is another of its outstanding qualities.

Inventor and scientist Ray Kurzweil predicted that by 2015 computing power would surpass the brainpower of a mouse, and by 2045 there would be more computing power than all of the human minds combined on earth (p. 96), which makes learning to speak machine an imperative need.

“The fact that computers can talk with each other means that they are collectively as smart as the most brilliant computer that they can access.”

Similarly, the social networks and tools we have created now connect us to an expanding network of knowledge and possibilities.

Whether in the real world or the computational world, connecting work is the catalyst for making changes happen at a scale that’s larger than just the doing work that an individual can perform. (p.89)

How can we figure out ways to collaborate and leverage the full power of our collective intelligence, inspired by how computing works?

I believe too, as Maeda affirmed in the book, that computers won’t replace us if we remain audacious.

We are creative, complex beings that have created (and are continuously creating) marvelous tools with technology and its special computational powers.

It really feels almost magical, although we are getting used to it by now, to be able to connect, learn, teach, communicate with, observe, and in a close future, possibly even feel, locations, people, and objects all around the world.

What a time to be alive.

References:

Maeda, J. (2019) How to Speak Machine. Penguin Publishing Group.